BOOK. Months and months ago I went looking through the section of ‘comic books’ in a central Copenhagen bookstore. Okay, not a very unusual thing to do, but this very day my eyes were caught by a cover which had quite a different drawing style than most of the other books in this department. Here it is:

Soon it became clear to me that the scenery on the front is inspired by the famous painting “Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer” - “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog” by the German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich (and I should know since I, years ago, had a roommate who owned a poster of exactly this painting, a poster he was extraordinary fond about. Wherever he put up the “Wanderer” was his home).

However, while Friedrich’s wanderer overlooks a sea of fog, this female hiker is gazing at a village. The woman is, of course, a drawing of Nora Krug, the author of the book, and the village beneath the cliff represents the place from which her and her family originates, her “Heimat”.

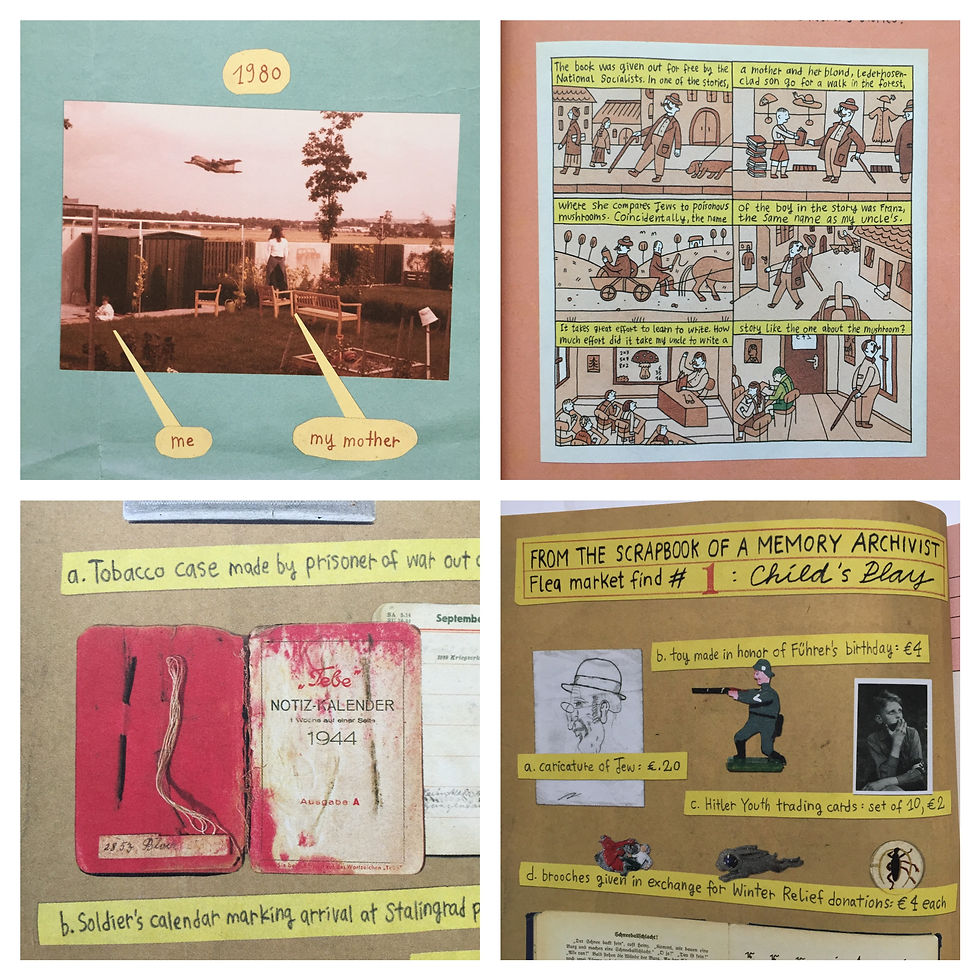

Well…at the bookstore I immediately bought the book, and I read it in only a few days - ’cause that’s what you do when you find an extraordinary piece of work, you just s-w-a-l-l-o-w it, right? Written in hand and formed like a scrapbook with photos, paper cuttings and drawings, every page of “Heimat” is a new experience, and it makes you curious to see what’s next - and next, and next.

Ever since my first reading the book has kept coming back to me, and not long ago, when I re-visited Krug’s website, I saw that “Heimat” has won a number of prizes, awards and ‘Best Of’s.

Let me just say: I’m not surprised. However, let me also say this: The “Heimat”-book is not only really well written and has great graphics too, it is also an important book that needs to be spread and kept alive in this world. Why I believe so I’ll let you in on right here.

Something had once gone horribly wrong

Nora Krug is born in the 1970s in south of Germany. She is a child of parents who entered their lives in the slipstream of WWII, but even so the war was not something her family ever really talked about. It was, most of all, treated as a great big secret, something the grown ups only debated, when the children were out of earshot. “Part of me understood that something had once gone horribly wrong”, Krug writes. But what that ‘something’ was she didn’t know.

Her state of ignorance changed, however, when she started going to school, ‘cause here Krug was taught about all the horrors her country had gone through in the 1940s. Her and her classmates were taken on class trips to concentration camp museums in France, Germany and Poland, she analysed a speech of Adolf Hitler, and she saw the documentation on how, in some German towns, the Allies, after the war, forced local farmers to drive the bodies of the dead Jews from the nearby concentration camp through the streets of the village for everyone to see.

Through the teachings of all the dreadful happenings, Nora Krug learned about the history of her country. But that was not all. She also learned that being a German was shameful.

Many years later Krug finds that this feeling of guilt still takes up room in her life, although she now lives thousands of kilometers away, in New York, and (by the way) is married to a Jewish man. When speaking English she tries to hide her German accent, and when doing her yoga class, she feels uncomfortable when she is instructed to lift up her right arm in an outstretched position, afraid that she might look like a German doing the Nazi salute.

However, besides carrying around a feeling of blameworthiness, Krug also starts wondering…’cause what about all the other sides there are to WWII and to ‘being German’ - other than the unsympathetic horror-ones? Why was she never taught at school about the tens of thousands of Germans that had been killed for resisting the Nazi regime? Or that 150.000 men of Jewish descent had fought in the German army? And why had they only been interviewing survivors of the concentration camps flown in from the US, and not learning about the experiences of their own grandparents?

There had been huge gaps in Krug’s education, she recognises, and because of these gaps she still doesn’t feel she knows who she really is. “How do you know who you are, if you don’t understand where you come from?”, she asks.

Following the trail of breadcrumbs

It soon turns out, though, that Krug’s lack of historical knowledge not only refers to the common German history - it also refers to the history of her own family.

So she sets out on a mission: From her childhood “Heimat” she will - using a reference to the German fairytale “Hansel and Gretel” - follow the trail of breadcrumbs through her mother’s and her father’s family history. Hopefully this search will lead her to a better understanding of the two related perspectives: Who she is as a person (formed by her upbringing), and who she is as a German of the postwar generation.

Was grandpa Willi a Nazi?

There is no doubt that Nora Krug’s project is ambitious. It leads her through dozens of archive papers and photographs, and to visits to the “Heimat”’s of her parents’ and grandparents’. But how does she know which breadcrumbs to follow exactly? Krug narrows her research down to 2 main focuses.

On her mother’s side she dives into the story of her grandfather, Willi. He worked as a driving teacher during WWII, but…

Was he also a Nazi?

In true detective manners Krug stubbornly searches for answers, and in a US military archive she finds Willi’s file. Among his papers there is a questionnaire that every German adult, living in the US sector, had to fill out after the war was over. The purpose of this was to investigate how the citizens had - or hadn’t - been part of political activities under Hitler’s regime, ’cause at this time Germany was (more or less) seen as a nation of Nazis where each and everyone supported “Der Führer”. “Trust none of them [..] The German lust for conquest is not dead”, a voice declares in a US War Department training film from 1945.

So in which category did Willi end up after ticking off boxes in the questionnaire? Was he among the ‘offenders’ or amidst the persons against whom all charges were dropped? Krug’s research takes you through some quite surprising facts, but what those are I will of course not reveal here ;-)

Franz-Karl and the skeletons in the closet

On her father’s side there is also one person who stands out from the rest, and that is her father’s older brother, Franz-Karl. This uncle of hers was a popular young man in his days, and a farmer who was set to inherit the family farm. However, in 1944 he “was killed by a shot in the chest while fending off an enemy attack”. At the time of his death he was only c. 18 years old.

Contrary to grandpa Willi there is not a shadow of doubt as to which side of the war Franz-Karl was on. Krug remembers that as a child she had learned not to feel sadness towards her uncle’s premature death since he had been one of Hitler’s soldiers. But now, as an adult, she wish to know: Who was he r e a l l y?

The search through her father’s family history is not only about war and political involvement, it is also a visit to a closet filled with skeletons of the troublesome family kind. Her father doesn’t speak to his sister and hasn’t done for years, and also he avoids spending time in his childhood town as an adult. Courageously Krug breaks through the invisible wall that exists between her father and his “Heimat”. She speaks with friends and family who knew her uncle and other of her relatives, and she learns things she didn’t know before. As she passes this information on to her father, she sees that he is deeply moved.

Putting together the broken pieces

So does Nora Krug reach the goals she had set from the beginning about getting a better understanding of her family history and of ‘being a German’? Well, at least she gets to a point where she recognises that “this is the closest she will ever get”. In my world that would be a mission completed.

She believes that her project has helped putting together at least some of the broken pieces that has been part of her own family history. However, she also acknowledge that although you fix something that once has been damaged, the cracks will still be visible (even if you use the strongest German glue in the world). You can not remove the scars of the past, but if you know what caused them there’s a chance you’ll at least accept they are there.

Certainly Krug’s Heimat-project has been of great importance to the history of her own family. But I’d think that several of her fellow citizens of the post-WWII generation also will recognize their story when reading her book - like the family secrets relating to the war that no one really talks about, the themes she raises on guilt and shame etc. And who knows, perhaps some of these readers will even start looking into their own inheritance, however painful it is?

There’s no doubt that historical awareness of WWII is needed, and not only on a personal level, ‘cause lately new cracks have begun to show. In 2017, Krug writes, the national election in Germany gave rise to a new right-wing party. For the first time in more than half a century the extreme right has claimed seats in parliament again.

In My Opinion

⭐ What I really like about “Heimat”

Firstly I need to say that I simply love the graphics of this book! The way the drawings, the photos, and the paper cuttings interact with the text. And the way all the effects are texts in themselves. When you read “Heimat” it’s kind of like watching a movie…and actually I believe that it would do very well if it was transformed into a documentary. But please! Read your copy of “Heimat” in such pace that you really get to s e e all the many many details that Krug has put into each page.

Another reason why I love the “Heimat” graphics is because I believe that when Krug is using this way of communicating her project, she reaches an audience who’d (probably) not read about historical themes like this otherwise. And that is a great accomplishment. (I wonder if there are any statistics about the audience of the book somewhere…?)

By writing her book, Nora Krug has shown me something I’ve never thought about: How - parts of - the post-WWII generation in Germany feel ashamed about their inheritance in their every day life. (Does the younger generation feel ashamed too? - I wonder). I’d like to think that Krug’s book gives some release to her fellow countrymen and -women, and that the shame will eventually shrink once out in the open for everyone to see.

Also “Heimat” made me aware how non-Germans also are keeping the horrible story of WWII and Germany/Germans alive in such a way that holds the next generation responsible for all things gone bad. Which is not fair. Fortunately more and more detailed knowledge about WWII sees the day of light these years, showing us that a war like that (any war…) only can be fully understood if it is seen from multiple angles. This is another reason why we need stories like Nora Krug’s, to help us add new and important details to the big picture.

📝 Some notes I made

It takes a lot of material to write a book like “Heimat”, and Krug has not been lazy - that’s for sure. So much interesting stuff here, and I’d say that she could easily have made 2 books of all the research done. And I’d be happy to read both.

Krug is good at opening small windows to side stories which connects to the main story - so that you understand the historical background for certain happenings, for instance. At times I’d wish that this walk down the ‘side roads’ were a little longer ‘cause I’m curious to learn some more.

Okay…I know I’m a map-fanatic, so of course I have to mention that I’d really like if Krug had placed a map of Germany somewhere. And that she’d list some of the main places she mention.

F U N F A C T S

✏️ Nora Krug is an illustrator - but she is also educated as a documentary filmmaker.

🏠 She is born in Germany, however, nowadays she lives in New York, US.

🗓 “Heimat” was published in 2018.

📚 Since then it has been translated to several languages….German, French, Swedish, Norwegian, Italian, Spanish, Danish.

👍 Time Magazine listed “Heimat” among ‘8 must read books’ anno 2018.

🏆 The book has won a number of awards, prizes and ‘Best Of’s.

💻 Visit Nora Krug’s webpage if you wish to know more: nora-krug.com

📽 Or watch this interview👇 where she speaks on the subject “Who I Am as a German” (made by ‘Louisiana Channel’ - Louisiana Museum of Modern Art).

See you next time.

Majken xx

P.S. If you like this blog post, please feel free to share it on your favourite social media, thank you 💛 See links for sharing below 🔗👇

P.P.S. If you have any comments on this blog post...or perhaps some recommendations of books, podcasts, movies, tv-series in the Historical Non-Fiction-genre? I'd love to hear from you! Please send me a message ➡️ C L I C K H E R E

This book review is based on Heimat - A German Family Album by Nora Krug. Particular Books, Penguin Random House UK, 2018.

Comments